for those who still believe in tenderness as revolution.

I. Prelude: 3:33 A.M

It’s the hour when ghosts come easy.

When the world forgets its weight for a while and the quiet returns like a first language, old and unpronounceable. I’m writing this at 3:33 a.m., wrapped in the kind of silence that feels like it could crack open a man if he’s not careful. Or maybe if he’s lucky.

Somewhere between the heartbeat of night and the breath that carries dawn, I am thinking about bell hooks. About the way her words arrive like a warm hand on the back of the neck. Not to pull you forward, but to steady you before you fall.

What does it mean to be worth loving?

Not just in the way the movies promise—body pressed to body under moonlight, declarations swelling like orchestras—but in the way that asks: Will you still choose me when I am inconvenient? When I am frightened? When I am not beautiful? What does it mean to be a man, a Black queer man, in a world that teaches you that love is both luxury and liability?

This is not a rhetorical question. This is a wound.

And bell hooks, saint of the tender and unspoken, gave me tools for stitching.

II. Encountering bell hooks

I met The Will to Change in a room of Black queer men in Atlanta—2019, summer thick and impatient. We gathered in a circle that felt more like ceremony than book club, all of us boys grown into men who still limped with the weight of unloved boyhood. That book was the first we read together. We did not know it then, but we were beginning the sacred work of returning to ourselves.

hooks met us where we bled and did not flinch.

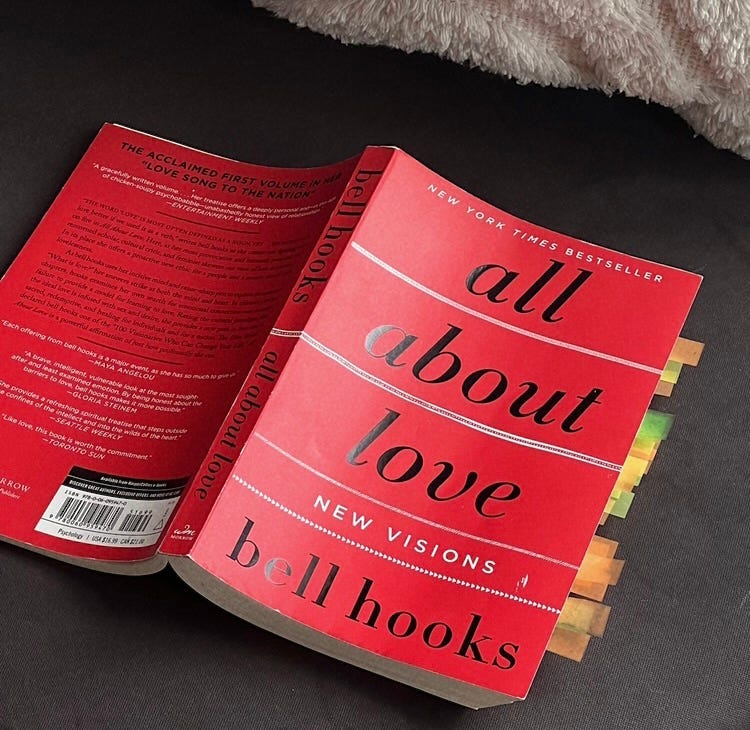

A year earlier, I held All About Love in my hands like scripture. 2018. I was thinking of proposing to the man I loved. I didn’t yet know that cancer would come and make ghosts of us both in different ways. But I was already shifting—growing out of the shell of emotional absence I had been taught to wear like armor. My faith was changing too, becoming something less tied to pews and pulpits, more like breath and fire, more honest.

I was finally proud of my queerness, not as decoration but as divinity.

bell hooks did not teach me who I was. She reminded me I had always been. And then she asked me to love myself enough to be better.

III. Love as Praxis

There’s a sentence in All About Love that lives in me like a second pulse:

“Knowing how to be solitary is central to the art of loving. When we can be alone, we can be with others without using them as a means of escape.”

It’s not a pretty line. It’s a mirror. And I’ve spent years looking into it.

Because before hooks, I mistook presence for love. I mistook proximity for care. I mistook need for intimacy. I had not learned how to sit with myself without fidgeting, without performing, without numbing the silence with noise or people or plans. I hadn’t yet developed the courage to meet myself in the stillness and not flinch.

But bell insisted. Love is not a noun, she told me. It’s a verb. A practice. A choice made daily. And if you cannot practice on yourself—what kind of love can you offer anyone else?

So I began to practice. With my breath. With the cashier at the grocery store. With friends who had forgotten how to receive tenderness without suspicion. With the parts of myself I wanted to banish.

She taught me that love is not transaction but transformation.

That it isn’t just candlelight and touch and sweet nothings. Love is confrontation. Love is accountability. Love is washing the dish you didn’t dirty. Love is listening even when your pride is loud. Love is returning—again and again—to someone else’s humanity, even when yours feels threadbare.

Love is not passive. It’s not soft in the coward’s sense. Love is the sharp edge of abolition. It asks you to unlearn cruelty. To lay down the weapon you were taught to become.

And still—and still—to be brave enough to reach.

IV. Masculinity as Loss

Patriarchy is a clever thief. It robs you slow.

Not in grand heists, but in the gradual dismembering of your softness. It teaches you to make your chest a vault. To hoard your tenderness. To flinch at your own longing.

In The Will to Change, bell hooks says, “The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead, patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves.”

I remember reading that sentence and going still.

I was a man by then—at least in the way the world understood manhood: deep voice, steady gait, capable of silencing his pain with practiced ease. But inside, something was breaking open. Her words cracked the armor I didn’t know I was still wearing. I began to trace the lineage of silence passed down to me like heirloom china: my grandfather’s stoic sighs, all of my uncle’s clenched jaw, the way I learned to say “I’m good” through a mouth full of unshed grief.

Men talk in codes. I love you becomes a nod. A slap on the back. A joke that veers too close to pain but never stays there. We’ve been taught to bury the map to our own hearts.

And still, bell hooks saw us. Not as monsters or projects, but as wounded beings taught to wound. She did not excuse harm, but she understood its architecture. She knew that healing men wasn’t about making us soft for softness’ sake—it was about making us whole.

To read hooks as a Black queer man is to feel the wound and the salve in the same breath. She loved us enough to demand better. She loved us enough to say: you do not have to be the worst parts of what you inherited.

V. Politics of the Heart

Love is not separate from revolution.

That’s what hooks insists, over and over, like a chorus. And I believe her. Because what else do we mean when we say abolition, if not the radical reordering of how we care for one another?

This country teaches us to love small. To love with conditions. To love only those who look like us, vote like us, believe like us. Love becomes a scarcity model—reserved for those who prove worthy through performance. And anything outside that—queer love, disabled love, poor love, Black love that doesn’t sanitize itself—is deemed dangerous.

But bell hooks would not let love be divorced from justice. She wrote of reproductive rights, of the silencing of trans voices, of the erasure of Black feminism from white feminist discourse. She wrote against war, against capitalism, against the commodification of our desires.

She knew that without love—real love, not the Hallmark kind—movements die. She saw the ways our liberation is not only about policy and protest, but about how we hold each other through grief. How we stay when it’s easier to leave. How we become refuge when the state becomes storm.

So yes, I think of her when I see trans kids being legislated out of their own names. I think of her when books are banned for daring to say Black people feel. I think of her when abortion is criminalized while guns are sanctified.

And I remember: love is political. Love is what they’re trying to burn.

VI. The Undersung bell

The world wants to flatten her into a slogan.

They quote All About Love in Instagram captions, print her name on tote bags, reduce her into the parts of her work that are easiest to swallow. But bell hooks was never safe. She was soft, yes—but softness can be seismic.

There’s a piece of hers called Inspired Eccentricity, where she writes about her grandparents, their strangeness, their defiant refusal to conform. It is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever read. In it, she says, “Living with eccentricity gave me the gift of constructive rebellion.”

It reminded me that to live outside the lines—to love outside them, too—is a kind of spiritual inheritance. A kind of salvation.

And Rock My Soul—that underloved, underread text on Black self-esteem—gave language to the ache that lives in our communities. She wrote of how we internalize the hatred hurled at us, how we survive by pretending we’re untouched. That book didn’t trend. It didn’t sell like her love trilogy. But it carried me in moments I couldn’t carry myself.

And Moving Beyond Pain, her brave critique of Lemonade, dared to say what many wouldn't: that even in our triumphs, we must interrogate how we commodify pain, how feminism can become costume, how visibility is not always freedom.

This, too, was bell hooks. Uncompromising. Loving. Unafraid to be inconvenient.

VII. To Live Like This Is to Love Like That

It’s 5:53 in the morning now.

The kind of hour where the body remembers what it cannot name. Where ancestors visit in dreams and grief walks the hallway like it still pays rent.

I sit in the stillness, bell hooks cracked open on my lap like scripture, and I wonder how many of us are awake right now—Black, queer, broken-open and rebuilding. How many are trying to love better than they were taught. How many are trying not to become the violence that raised them. How many are practicing presence with trembling hands.

This is what bell taught me: to love is to live alert to the world’s fractures and still choose tenderness.

To love is to imagine otherwise.

Not only for ourselves, but for the ones who come after. The ones whose names we do not know yet. The ones born into systems we are still dismantling.

Some nights, I think of that book club in Atlanta. A circle of Black queer men, each of us heavy with our own ghosts, reading The Will to Change like it might save us. And maybe it did. Maybe not all at once. Maybe not in ways we could name. But something softened. Something shifted. And we looked at each other with new eyes.

Some days, I return to the moment in 2018 when I held All About Love in one hand and a ring box in the other, imagining a future that would never come, at least not like that. And even then, hooks was there—not to cushion the fall, but to teach me how to land with grace. How to let grief be proof that I had dared to love in a world that counts that as rebellion.

Because it is rebellion.

To say: I will not inherit your silence.

To say: I will not offer shame as inheritance.

To say: I will hold my beloveds with care, not control.

To say: I will make room at the table for the kind of love that changes everything.

And when I falter—because I do—when I speak with a sharpness I learned from men who did not know how to be soft, when I close the door out of fear instead of faith, I return to her pages like psalms.

bell hooks is not a saint. She did not write for worship. She wrote for transformation.

And transformation is a brutal, beautiful thing.

It asks you to tear down and rebuild. To question your gods. To sit with your sorrow. To forgive what you were never given. To stop mistaking trauma for tradition. To stop offering domination as devotion.

Her work isn’t finished. It never will be.

Because as long as there is a Black child somewhere learning to hate their own reflection, as long as a queer boy is told to make himself smaller, as long as a mother goes unheard, as long as systems claim our bodies but not our brilliance—bell hooks lives.

In the way we hold each other.

In the way we weep without shame.

In the way we love without apology.

VIII. A Love Letter for the Living

I don’t write this because I understand bell hooks fully. I write this because I am still trying.

Because to read her is to begin again.

And again.

And again.

A love ethic, she said, is the foundation of justice. Not sentiment, not softness, but a rigorous commitment to the well-being of others. Even when it’s inconvenient. Especially when it’s inconvenient.

This is how we build a world worthy of our children. Not by perfecting the self, but by practicing the kind of love that reshapes the self in relation to others.

So if you ask me what bell hooks gave me, I’ll say:

She gave me the courage to unlearn.

She gave me language for the ache I used to carry like scripture.

She gave me permission to hold my queerness like a hymn.

She gave me back my heart—not polished, but whole.

And if you are reading this at 6:00 in the morning, as the world continues to grind against the tender parts of you, know this:

You are not unlovable.

You are not alone.

You are part of a lineage that says love is more than survival—it is salvation.

And we’re not done loving yet.

Amen on this corner.

“The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead, patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves.” This touches me deeply, as a mother of three sons who have struggled against these forces all their lives. That they have come out on the other side tells me something about who they’ve become and I’m proud to be in their presence. Thank you for sharing your own battle. You are a gift!

“Black, queer, broken-open and rebuilding,” and simply beautiful.