Editor’s Note:

This letter began as a response to a beloved friend and fellow believer, Stephon Bradberry, whose May 28th meditation on regard raised the kind of questions that don’t deserve quick replies. So I wrote this instead, a conversation between faith and fire, between the ruin and the bloom. May it reach you wherever you are. May it ask something of you too.

Beloved Stephon,

I write you in that hour where silence does not beg for company but for truth. It is deep night now. The kind of night Baldwin once said made him long for a witness, even when none could be trusted. I waited to write not because I lacked words—but because your letter demanded more than reaction. It asked for meditation, a reckoning. So I sat, and I listened. And when the time was right, I lit a candle and began.

First, let me say thank you. Not simply for responding, but for responding with the same gravity, care, and rigorous regard you’ve always extended toward me. I do not take that lightly. In a world spinning faster toward amnesia, where so many speak to perform and not to be understood, your letter felt like Sabbath.

And yet, I must tell you on this second breath of Pride Month, beneath stars that still believe in our becoming that I have reimagined the faith of which you have written.

You asked questions that don’t settle—they haunt the air, cling to the corners of quiet rooms, tap your shoulder when you’re trying to sleep. What do we do with our faith, our values, our God, when the world is collapsing in slow motion around us? When harm doesn't just happen but repeats itself like it was choreographed. When safety becomes a luxury, and the soul feels like it’s being evicted from the body it trusted.

I want to sit with each of your questions, not like I have answers, but like I have skin in the game. Because I do. We do. And, if I don’t speak back, the silence itself becomes complicit.

So I’ll begin here—with regard. Not just the noun, the state of being seen or held in esteem. I mean regard as a practice, as ritual, as stubborn Black survival. You mentioned your neighbor who was startled by how often you speak to people on your walks. That startled me too—not her question, but how familiar it is. I’ve been that person on the other side of your gaze. Walking Jimi, offering regard to the world and wondering if it will offer anything back. I grew up being told to “speak when you enter a room,” not as manners, but as theology. If someone was breathing, they deserved acknowledgment. That was the gospel of my great-grandmother, a factory worker with middle school reading skills and postdoctoral wisdom in human dignity.

But the older I get, the more I see that regard, especially from the most disregarded, is revolutionary. Because to regard someone is to recognize their soul before you know their name. And this world? This world profits off our forgetting. Forgetting how to look one another in the eye. Forgetting the sanctity of a neighbor. Forgetting we are not machines or commodities or case studies.

I think of bell hooks here—her insistence that love is an action, an ethic. Regard is one of the first actions of love. It’s how we let someone know, “You matter because you are.” Not because you produce, not because you perform, and not even because you believe; just because you are.

And yet, we don’t get to live in that ethic uninterrupted. We’re constantly navigating harm and the limits of our love. So let’s go there, too.

You wrote that choosing your values over your safety is a kind of risk your ancestors taught you. That line echoed, beloved. I felt it in my spirit.

I’ve wrestled with that risk all my life—sometimes knowingly, other times only in hindsight, when the bruises bloomed or the loneliness made itself too comfortable in my ribcage. The values that I hold: abolition, love, truth-telling, and communal care, have cost me comfort, relationships, and illusions of protection. And yet I could not forsake them. Not because I’m brave, but because somewhere along the way, I came to believe that safety divorced from integrity isn’t safety at all, it’s just hiding. And I’ve hidden enough in this life.

It’s not a romantic thing, this choosing of values. Sometimes it’s gut-wrenching. Sometimes it’s standing alone in a room full of people you love and realizing that none of them would speak up if harm came for you. Sometimes it’s walking away from a job that pays you but starves your soul. Sometimes it’s looking someone you once trusted in the eye and saying, “No, not this time.”

And yet—what else is faith if not living into a truth that might never protect you but still makes you free?

Audre Lorde warned us that our silence will not protect us, and I believe her. But what I didn’t understand until recently is that even speaking, especially from the margins, might not protect us either. The world doesn’t love prophets. Especially not Black, queer, soft-hearted prophets who dare to ask for more than survival.

So we learn to live in the tension, the refusal, the ache. We learn to stretch our values wide enough to include our own safety, even when the world won’t.

But what happens, then, when harm doesn’t come from the outside? What happens when it shows up wearing familiar faces, calling itself community? That’s where the cut goes deepest.

I’ve been betrayed by people who said they loved me in the name of “what was best for their pockets or proximity to power and influence.” I’ve watched harm get shuffled under the rug of urgency, watched queerness silenced in church basements that claim to be liberationist. I’ve stood in rooms that applauded freedom but couldn’t stomach the mess of healing, the slowness of truth.

And I’ve done harm, too. In my silence, in my fear, in my fatigue. There are things I can’t take back, things I’ve had to confess in prayer and poetry because the people I hurt weren’t always around to hear it. Grace has become a language I’m still learning to speak, especially toward myself.

bell hooks once said, “Rarely, if ever, are any of us healed in isolation. Healing is an act of communion.” But what if the communion table has splinters? What if the people sitting beside you are the ones who broke you? What does healing look like then?

I think healing starts with not pretending. With telling the whole truth, even when it implicates the people we love, the movements we’ve given our lives to. We cannot keep building futures on top of unspoken harm. That’s how trauma becomes tradition. That’s how cycles survive.

So I wrestle with this: how do we become communities where harm can be named, not buried? Where accountability isn’t a death sentence, but an invitation?

Sometimes I imagine the Christ not just flipping the tables, but sitting at one, looking each of us in the eye, saying, “Tell the truth. All of it. And then let’s begin again.” That’s my reimagined gospel. Not one of punishment, but of process. Of confrontation that doesn’t cancel, and forgiveness that doesn’t forget the wound.

Because if redemption is to mean anything, it must mean we are capable of more than repeating the same damn mistakes.

There was a time I believed, or at least wanted to believe, that we could mend the broken systems from within. That if we entered the rooms with our spines upright and our tongues sharp with scripture and truth, if we spoke in a register the powerful understood, be it legislation or decorum—they might hear us, and something might give way.

But the older I get, the more I feel the rot in the foundation. The cracks are not accidental. They were designed that way—fault lines carved by white supremacy, imperial greed, and Christian nationalism masked as morality. What we keep calling “broken” was never built to hold us. It was designed to break us on purpose.

Still, I understand the pull. We are a people of incredible hope, even when hope feels like a betrayal. Even when we know Pharaoh’s palace wasn’t meant for us, something in us still dreams of slipping in through the side door and sneaking the blueprint out. We still imagine that maybe—just maybe—we can make it kinder.

But what do you do when the machine is working exactly as intended?

You asked about faith. And I have to confess: I’ve lost faith in systems, but I haven’t lost faith in people. I believe in our capacity to imagine and birth new ways of being, even when everything around us demands obedience to what already is. I believe in our sacred defiance.

Because fascism doesn’t begin with tanks or overt laws—it begins with silence. With the quiet accommodation of cruelty. With the normalization of cages and the flattening of language. With churches that refuse to call police violence a sin, or schools that erase the very history that shaped our scars.

It begins with metaphors—woke, thugs, illegals, super-predators, “savages,” language that strips away our humanity until what’s left can be bombed, deported, sterilized, or shot without consequence.

And it is everywhere. Fascism is not waiting in some distant dystopia; it is already here, wearing the badge, the robe, the presidential seal. And still, some will ask us to be civil. To make our case with respect. To be patient, even as the noose tightens.

To that I say: No. Respectability has never saved us.

I think of Daniel in the lions’ den, not as a cautionary tale of obedience, but as a lesson in principled refusal. Daniel didn’t pray quietly in private. He prayed in the open window, knowing full well it could cost him everything. That, to me, is faith: not the absence of danger, but a declaration in the face of it. A refusal to worship what devours.

And so we resist. Not because we are naïve, but because we remember who we are. Because we carry with us the sacred memory of Harriet’s hush songs, of Baldwin’s unflinching eyes, of Sylvia Rivera tossing truth into the fire, of Marsha throwing a brick. We resist because we must.

But here’s the part I rarely say out loud: resistance alone is not enough. If we do not pair it with vision—if we do not root it in love, in imagination, in the possibility of a world beyond punishment—we risk becoming mirror images of the very thing we’re fighting.

We cannot simply say “tear it all down” without also asking, and then what? That’s where my faith lives now—in the messy, hard, necessary work of the and then what.

There are days I wonder if God is just watching from a distance, not out of indifference, but exhaustion. And then I remember: we are the only hands God has left.

God is not elsewhere. God is here, in the mess, not above it. Not a distant judge or aloof creator. God is cracked open in the living room where a mother counts eviction notices. God is on the subway bench, curled up beside the man whose family stopped calling. God is in the prison yard where someone is learning their own name again. God is in the alley behind the nightclub, whispering to the boy with glitter in his beard and shame under his tongue: you are still mine.

The idea of a God who only dwells in the clean spaces—the pew, the pulpit, the Sunday clothes—that God never made sense to me. I need a God with dirty feet. A God who sweats. A God who bleeds. A God who knows what it means to be misnamed, misgendered, misunderstood. I need a God who does not hide from my grief or my rage. Who doesn’t ask me to tidy up before entering the room. And I need that God to regard me.

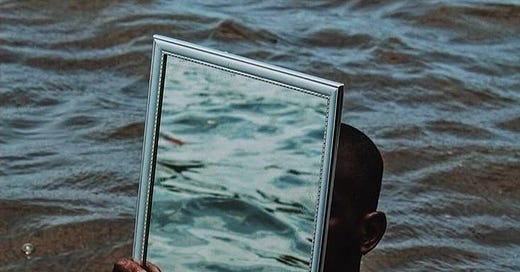

That word you used, regard, pierced me. There is something holy in being seen with gentleness. Not just noticed, but regarded—the way a mother cups her child’s face, the way a lover says your name when you’ve forgotten how to answer it. That kind of seeing is rare in this world. We are too often surveilled, but not regarded. Watched, but not witnessed.

That is why daily love, to me, is a form of worship. Lighting a candle not to cast out darkness, but to make room for presence. Making tea with intention. Holding the door for a stranger, not as obligation but an invitation. Calling my little brother just to hear how he breathes. Kissing my own hands before sleep because they carried me through another day. These are not small acts. These are sacraments.

You wrote that you sometimes struggle to believe in a world remade. Me too, Beloved. But I find fragments of it already here, in the ways we hold each other when the state will not, in the way your letter held me, in the way this conversation, this sacred correspondence, is itself an altar. There is God in that.

And maybe that is enough for today. Maybe that is the miracle: not that we are unscathed, but that we are still here. Still trying. Still loving with whatever fragments we have left. Still choosing to be human when the world tries to reduce us to functions or threats or statistics.

And maybe that’s what salvation actually is, not escape, but encounter. Not being lifted out of the fire, but held within it, so we don’t burn alone.

You asked—what do we do with harm in community?

And I think of the time my great uncle slammed the door so hard it cracked the frame, not out of anger at me but at the ghosts clinging to his back. I was thirteen. I flinched. He wept. Later that night, he made me tea and sat across from me in silence, his hand trembling as it reached for the sugar. We never spoke of it again.

That was the first time I learned that some apologies are given without words. And that some wounds scar in silence.

But silence is not always safety.

It is a strange thing to be hurt by those who are supposed to hold you—and even stranger to still want their healing. Our movements are full of the walking wounded. We preach liberation while bleeding on each other. We chant about abolition but excommunicate like the churches we fled from. We gather to sing about love, and then weaponize it when someone’s harm rubs up too close against our own.

It’s easier to talk about systems than siblings. Easier to critique the state than to sit with the one who lied, or stole, or didn’t show up when we needed them most. And yet—this is the work.

bell told us love is an action, not just a feeling. I’d add: accountability is an action, too, not just a sentence. The question isn’t whether someone deserves forgiveness or whether harm happened. The question is: can we build a world where repair is possible? And even more radical: can we do that without discarding people like trash?

That’s what abolition is teaching me, not the absence of consequence, but the presence of care even when it’s hard, even when it’s costly, and especially when it’s close.

I think of the friend I cut off too quickly because I was more fluent in boundaries than in restoration. I think of the family member who hurt me deeply, and how I still keep their birthday saved in my phone. I think of the many rooms where we don’t speak of the harm we’ve caused because we are terrified of what naming it will do. But if we don’t name it, how can we heal?

I don’t want a justice that only exists on paper. I want a justice that can sit in a kitchen at 2 a.m. and say, “I did harm. I’m still learning. Can we begin again?”

That doesn’t mean everyone stays close. Distance, too, can be holy. Boundaries are not banishments, they are invitations to return rightly. But we need more rituals of return. More pathways back to each other.

And that’s where your final point leads us: redemption.

I’ve wrestled with that word. As a queer Black person who knows so many of my friends who were raised in a church that loved them best when they were silent, I’ve had to remake redemption in my own image. I no longer believe it means being cleansed or erased or made palatable. I believe it means being seen as whole, even when still wounded. It means believing that no one is beyond reach, not the ones who hurt, not the ones who failed, not even the ones who look like our enemies. That’s the scandal of grace. That’s the fury of love. It refuses to write people off even when writing them off feels safer.

But redemption cannot happen without truth. And it cannot be coerced. It is chosen. Slow. Earned in sweat and contradiction. It does not mean we are owed trust again, or a platform, or presence. It means we are still human, still sacred, still capable of becoming.

And isn’t that the gospel we’ve been trying to live all along? Not that we escape the ruins, but that we build altars in them. Not that we are perfect, but that we are possible. Again and again and again.

I return to where you began, with your question of faith in broken systems.

And I confess: I do not know if I have faith in them. Not anymore.

Not in the system that let my mother die waiting for care. Not in the ballot box, that sometimes feels more like a performance than a promise. Not in the prison-like shelters they call “housing,” or in the churches that call themselves sanctuaries, but exile the most tender among us.

But I do have faith in the refusal.

In the refusal of poor Black mamas who feed the whole neighborhood off EBT and prayer. In the refusal of trans femmes who still walk down the block like it's a runway, even though the world has made them a target. In the refusal of the formerly incarcerated brother who teaches abolition to middle schoolers and calls it hope work.

I believe in that. That is my liturgy now.

You asked about values versus safety, and I felt the knife twist inside me. Because sometimes our values put us at odds with the people we love. Sometimes, they put us in harm’s way. And sometimes, choosing our values feels like walking into fire without a shield.

But I think of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, not as a lesson in faith alone, but as a parable about collective defiance. They walked in together. And when the flames rose, they were not consumed. That’s what I want: not safety as a product of compromise, but safety as the fruit of communion. Not protection from harm through silence, but protection from erasure through truth.

I don’t believe safety and values are opposites or competing. I believe the world has taught us to treat them as such. But in the deepest sense, safety is what our values are for. A world where the most vulnerable are free to be whole, to be seen, to be loud, to be soft. And when harm comes, as it inevitably will, our values are what help us respond, not with punishment or exile, but with clarity, with consequence, with care.

So no, I don't have faith in the system. But I do have faith in us.

My faith is rooted in the makeshift communion of mismatched radicals and tired prophets, and holy doubters. In the ways we gather after funerals, and cook too much food, and name our children after people the world forgot. In how we keep loving each other even when the world tells us to harden. In how we come back to each other, not always perfectly, but persistently. And that, to me, is where God, the divine they/them lives now.

Not in the high pulpits or the whitewashed capitals, but in the people who refuse to give up. Who weep and still sing. Who break and still build. Who write letters like yours, and invite others into the wrestling.

That’s what you’ve done here, my friend. And I thank you. I don’t have answers, only echoes. Only fragments and firelight. But I hope this letter finds you like warm water meets tired hands. I hope we keep building this language together, messy as it is.

The psalmist wrote,

“The stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.”

Let us build our altar there.

In faith and fire,

Saint Trey

If this moved you, pass it forward.

Comment, share, or write your own letter in response. We build by listening back.

To read Stephon Bradberry’s original letter, visit: Meditation on Regard, in Response To Your Questions.

This was so beautifully and carefully written. I'll probably spend the day thinking about it before offering more commentary because, as you so eloquently stated, it doesn't deserve quick replies. Though, it does remind me of a conversation with my line sister some years ago. When we met, she stated, "I always thought you were weird, waving to me on campus, like who is this girl." And, it was always just regard. Thank you for writing this.

Thank you for this letter. It gave me goosebumps by the second paragraph and soon I couldn’t hold back the tears…tears of everything. Frustration and fear, certainly, but also Hope and strength because these “simple” actions are so profound and POSSIBLE. Regard! Let us see each other and not flinch away. Redemption! To sit together with the hurt and work to find a way through…

Also, I felt recognition - although we perhaps don’t share any “identity labels” besides “humans” - because here, in words for the first time, are some of the deepest, animating values of my core. It’s more important than ever to live them and bring them into our little pockets of the world. But it’s also scarier; your letter urges me to meet this moment with the courage humanity deserves.

As Ruth Jean-Marie commented, I too will long sit with these words… Again, thank you.