I. Reimagined Prayer

God of Donkeys and Dirt Roads,

God of Grandmama’s hands and blood that won’t dry,

Come ride into this aching world again

not with triumph,

but with dust on your feet

and the fire of the forgotten on your breath.

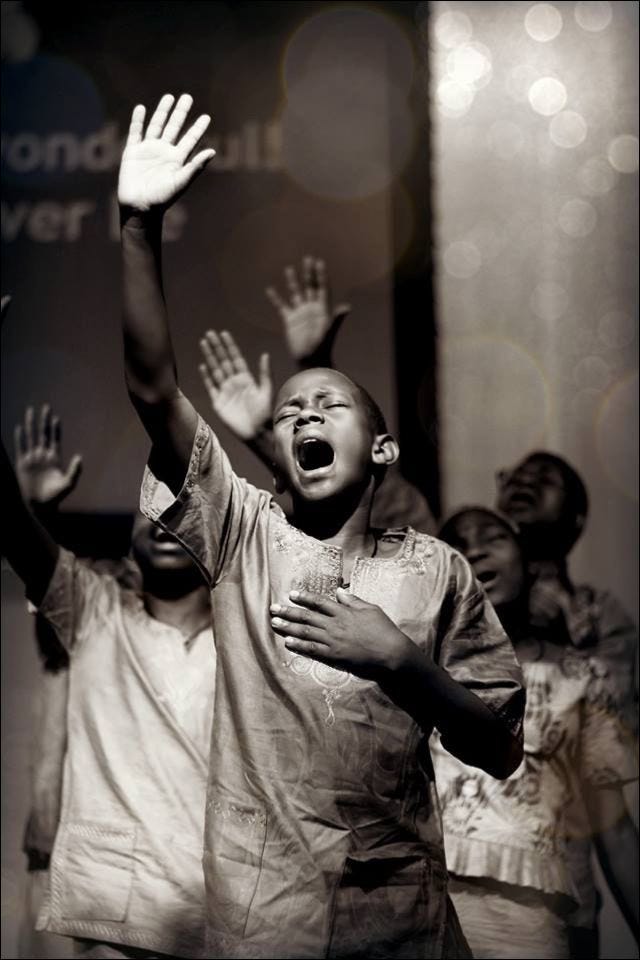

God of chain-gang psalms and back-pew prayers,

of the girl who kissed her love behind the choir stand

and the boy who danced too free

call them holy again.

Come low, like breath after drowning,

like Harriet’s whisper: go.

Come Black-eyed and barefoot,

with prayers that sound like grief.

We don’t need silk.

We need sweat.

A savior who limps.

One who waits beside us

as we bury one more name

the world refused to spell right.

Enter like truth.

Like fire.

Like us.

Let us say amen with our broken shoes,

amen with our tired mouths,

amen with our fists unclenched

just long enough to hold each other.

Amen.

And again

amen.

II. Procession of Disillusionment

This year, the palms feel heavier in our hands. Not a symbol of celebration, but something closer to a funeral fan. We wave them not in triumph but in mourning, not to cheer a king, but to cool the fire grief has left behind. Palm Sunday was never just about praise, it was also about the dissonance. About how people can cry “Hosanna!” while empire sharpens its knives just beyond the city gates. About how hope can be shouted through cracked lips, even as the cross waits like a shadow on the hill.

This is the procession we find ourselves in now.

What does it mean to cry out for liberation when the world feels too numb to listen? Or worse, when those around us have learned to bow so deeply to the empire, they no longer remember what it means to stand?

Gaza is burning. Not metaphorically, literally. Children are pulled from rubble, dust in their hair, blood drying on their fathers’ hands. The silence of the so-called civilized world is louder than the missiles. Book bans are sweeping through libraries and classrooms like a second burning of Alexandria, this time aimed at Black memory, queer bodies, Indigenous truth. The stories that saved our lives are being stripped from shelves by people who’ve never had to fight for a single page.

In this country, women’s bodies are under siege, legislated like land, controlled like property. Our trans siblings disappear—either by violence or neglect—and the world barely whispers their names. Anti-Blackness continues to shape every institution, every breath, every assumption of guilt. We are hunted in police reports and hospital charts, in welfare lines and school suspensions. And still they ask why we are angry?

And then there was the election, another ritual dressed up as hope. But for many of us, the ballot box feels more like a mausoleum, where we lay our beliefs to rest and try to convince ourselves that choosing the lesser of two evils is somehow salvation. We vote not because we trust the system, but because our ancestors bled for the chance to demand something better. Even if better never comes.

In the midst of it all, Palm Sunday arrives. And we walk, just like the crowd did then. Some cheering. Some crying. Some unsure of what they’re even reaching for. And yet we keep reaching. Because deep in our bones, we remember what it means to believe even when belief feels foolish.

Liberation doesn’t always look like a miracle. Sometimes it looks like marching anyway. Like praying through clenched teeth. Like saying “Hosanna” not because you think salvation is certain, but because you refuse to let despair have the final word.

The road to Jerusalem is also the road to the cross. And Black people, queer people, poor people, we have always known how to walk toward danger with our heads held like prophecy. The question isn’t whether we will survive the empire. We’ve already outlived so many. The question is how we carry our palms—with grief, yes, but also with a holy kind of defiance.

III. Cole Arthur Riley + The Jesus on a Donkey

“There is miracle in belonging to a God who rejects the image of a glorified hero and instead comes to us on a donkey, centering the plight of those who suffer. Liberation begins with this: Do not be afraid.”

Cole Arthur Riley wrote that, and I keep returning to it this morning like breath. Not for comfort in the soft sense, but in the sense of oxygen, what your soul inhales when the air around you has been thinned by empire.

There is something dangerous in how Jesus has been inherited by the West. Stripped down, starched clean, turned into a mirror for empire to behold itself with pride. A weapon carved from scripture and crowned with whiteness. But Riley’s line reaches through that fog, holds our faces, and turns them back toward the truth: that Jesus never rode in on a warhorse, never moved with spectacle, never came to occupy. He came low, in dust and breath. He came in the posture of resistance. On a donkey, not a tank.

There is nothing accidental about that choice. The donkey is deliberate. It’s slow, unimpressive, working-class. A beast of burden, not a symbol of might. It walks like the poor walk: with no rush to transcend the ground, no shield from the dirt. And so God enters the story not from above but from beneath, through the aching lives of those Rome would rather forget.

This Jesus was not a sanitized savior but a brown-skinned, calloused-handed, Jewish radical who lived under occupation, knew the taste of poverty, and chose not to ascend but to descend into the deepest wound of his people. That is the Jesus Riley is pointing to. The one who doesn’t court power, but touches lepers. The one who flips tables. The one who cries.

And this is where my own theology starts to breathe.

The Blood I believe in didn’t stain flags or build thrones, it bled beside the condemned. It ran down a criminal’s cross, not a general’s chest. It cried out from prison floors and kitchen sinks, from protest lines and refugee camps, from bedrooms where survival was a quiet act of faith.

If God rode in on a donkey, then liberation must begin with slowness. With humility. With proximity to pain. Not as charity, but as kinship. Not to fix, but to feel.

The Jesus I trust isn’t coming to drape himself in gold or write laws in marble. He’s coming to sit where we’ve been sitting. To hold the hand of the terrified. To whisper don’t be afraid not because there’s no reason to fear, but because we are not alone in it.

This isn’t mythology. This is gospel.

It is, as Morrison might say, the function of freedom. Not to live above suffering, but through it. Not to escape the fire, but to walk through it with hands unclenched.

So if Palm Sunday is a procession, let it be one where we know who we’re following. Not a king who came to conquer, but a God who came to weep. And the miracle is not that he saves us from suffering, but that he enters it with us, again and again, dust on his feet, justice in his mouth, riding slow, riding low.

And saying: Do not be afraid.

IV. Personal Reckoning: Why I Still Believe

There have been moments I should not have survived. Not in metaphor, but in the trembling of the body, the stammer of breath that refuses to steady, the nights where I tasted the end and could not find the will to call it by name. There were pills lined up like a prayer I didn’t know how to finish. There were mornings I woke up angry that I had.

And still—I believe.

Not because belief was handed down like a clean heirloom, polished and untouched. No, mine came cracked. It came through my grandmother’s hands—calloused, steady, stained with grease and grief. She sang hymns while caring for others who loved like me in hospital , while picking collards, while burying her sister at just 31. She never called it theology, but she knew something about survival. About a Jesus who visits kitchens before cathedrals.

I remember Sunday School, with its glossy paintings of a blue-eyed Christ and tidy miracles. But I also remember the unease. The way something in me twitched when they said “everyone” but didn’t mean us. When they told me to “be still” and I heard, instead, be small.

So I started asking questions. About hell. About sex. About what it means to be loved by God when the church can barely say your name without wincing. And those questions didn’t kill my faith. They saved it. Because I needed a God big enough for my terror. Tender enough for my truth.

I’ve seen Jesus in the face of lovers who held me in the dark, not asking me to change, only to breathe. In the stranger on a subway who placed their hand on my knee and said, “You gon’ be alright,” with the authority of an angel. In the whispers I couldn’t trace, but which kept saying, Not yet. Stay.

I don’t trust easy. Not the body politic, not pulpits, not promises wrapped in patriotism. I’ve watched them betray the most beautiful parts of us. I’ve watched them legislate cruelty and call it righteousness. I’ve felt the fatigue that comes from trying to hold hope in a land that profits from despair.

But here’s the thing.

I still believe. Not in a sanitized Christ, not in a God who watches from a distance, arms folded. I believe in the One who keeps showing up in protest chants and porches, in queer love and in refusal.

The God who sits with the weeping and doesn’t rush them. The God who loves me in my softness and my fury. The God who doesn’t need me to be clean, only honest.

Faith, for me, has become less about certainty and more about fidelity. Not answers, but presence. Not perfection, but return.

And I keep returning.

Because somewhere beneath the rubble of doctrine and dogma, I still hear a voice calling my name—not to shame me, not to save me, but simply to say: I see you. I’m here.

And that, somehow, is enough.

V. The Danger of Contentment

It’s a strange thing, how we learn to make a home in the very place that once tried to break us. How the body aching and wise, can be tricked into calling chains a kind of jewelry, as long as they glint in the right light.

This is the danger of contentment.

Liberation is coming. But not everyone will recognize it when it rides in slowly, covered in the dust of the oppressed. Some will miss it because they’re too busy shining their medals. Others because they’ve mistaken the comfort of familiarity for the presence of God.

I worry about us. About how easy it is to slip into forgetting. To mistake progress for peace. We’ve been told to be grateful for how far we’ve come, as if time alone unravels injustice. As if history moves forward without our hands dragging it there, bloody and blistered.

But empire is clever. It has learned to smile now. To market itself as diverse. To host panels and quote Baldwin. To let you sit at the table—as long as you don’t flip it. This is how power survives: not by brute force alone, but by convincing the bruised that the beating has stopped.

There is danger in neutrality, in pretending that silence is wisdom. There is danger in the slow dimming of outrage, in the way some of us begin to decorate our cages, hang diplomas on the walls, take selfies beside the bars.

Freedom doesn’t always look like fire. Sometimes it looks like the absence of applause. Sometimes it’s walking away from a platform. Sometimes it’s the decision to speak plainly when everyone else is performing fluency.

Liberation isn’t always loud. Sometimes it’s limping. Sometimes it’s invisible to the eyes trained by spectacle. But it’s still coming.

And when it arrives, don’t expect it to be clean. It won’t be led by influencers or announced with theme music. It won’t smell of perfume. It will reek of sweat and survival.

So we must stay awake. Must refuse the seduction of being liked by systems that depend on our forgetting.

Because the moment we get comfortable, the moment we start measuring success by proximity to empire rather than by our closeness to truth, we lose the thread. We betray the ones who bled so we could breathe a little freer.

And what is contentment, if it costs us our conviction?

I am not at peace. And maybe that’s okay.

Maybe that’s the proof that I am still alive.

VI. Liberation Is Coming

Hope, if it means anything, must be forged in fire. Not the kind that burns indiscriminately, but the kind that refines. That clears away illusion and makes room for what might be holy.

Liberation is coming. Not as a myth, not as a metaphor, not as the dangling carrot of some celestial reward, but as a truth with dirt beneath its nails and breath in its lungs. It is policy. It is protest. It is poetry. It is presence.

And it is already among us.

Palm Sunday, for me, is no longer about palms. It’s about memory. Resistance. A procession not of praise alone, but of prophecy. We march not because we believe the road will be easy, but because we remember the One who walked it anyway, with no sword, no armor, just love and a borrowed donkey.

The crowd may not wave branches this time, but we’re still here, laying down our coats of grief and joy for something greater to pass through us. We are still clearing the way, with our cracked voices and tired feet, with our refusal to be satisfied by symbols when we were promised substance.

And this is the charge: do not wait to be rescued. The sky is not going to split open just to distract you from the work of becoming.

Liberation is not later. It is not elsewhere.

It is now, in the policies we demand, in the bodies we protect, in the language we unlearn and the joy we practice.

It is in the auntie who feeds a protest line with borrowed pots.

In the teacher who slips a banned book into a student’s hand.

In the trans kid who keeps walking to school, head high, every day they’re told they shouldn’t exist.

In the Black boy who dances anyway.

In the undocumented mother who names her child freedom and means it.

Liberation is not something you inherit. It is something you build, again and again, even with shaking hands.

It is personal, political, communal, spiritual. It touches policy and prayer. Touches housing and healing. It shows up in ballrooms and in backyard conversations.

And I believe it is coming, not because I’ve seen the signs in the stars, but because I’ve seen it in you. In the quiet ways we keep showing up for one another. In the fire that hasn’t gone out.

This is my prayer:

That we remain tender in our rage.

That we become ruthless in our love.

That we refuse every empire that asks us to forget our sacredness.

And that when Liberation does come, riding low, walking slow, dust-covered and still divine we won’t be caught sleeping.

We’ll be standing at the gates of our neighborhoods, arms outstretched, voices ready, saying:

Welcome. We’ve been waiting.

VII. Benediction

Go now, not in silence, but in knowing.

May you be the one who names the empire for what it is, even when it smiles at you, even when it pays you well.

May you not confuse its golden gates with glory, its monuments with memory, its peace with justice.

May you remember that God did not choose a palace. God chose a borrowed beast and the trembling hands of the poor.

May you ride low, with the wounded.

May you walk slowly enough to hear the brokenhearted breathing beside you.

May you carry the sacred in your bones, not in your performance.

And when the world tells you to worship power,

May you remember the God who came with no sword,

Only breath. Only blood. Only love.

This is not the kind of hope that waits politely.

It is the kind that flips tables.

The kind that mourns loudly.

The kind that survives and still sings.

So may you rise like that.

May you speak like that.

May you love like that.

And when the procession comes again, not with palms, but with protest signs, and poems, and children holding each other like gospel

May you not just stand on the sidelines.

May you lay down your coat.

May you lift your voice.

May you make way for Liberation.

It is coming.

It is already here.

It lives in you.

Amen. Amen. Amen.

As an atheist that grew in black households that practiced Christianity, this might be one of the most brilliant pieces I’ve read in awhile. The unapologetic truthfulness within this needed to be said fr.

This is one of the most powerful essays I have read on this platform. I am saving it and will keep it for the times ahead. Thank you so very much for sharing your words and your truth.