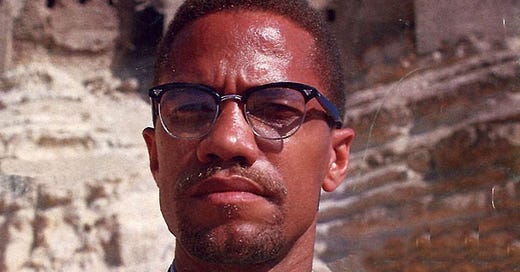

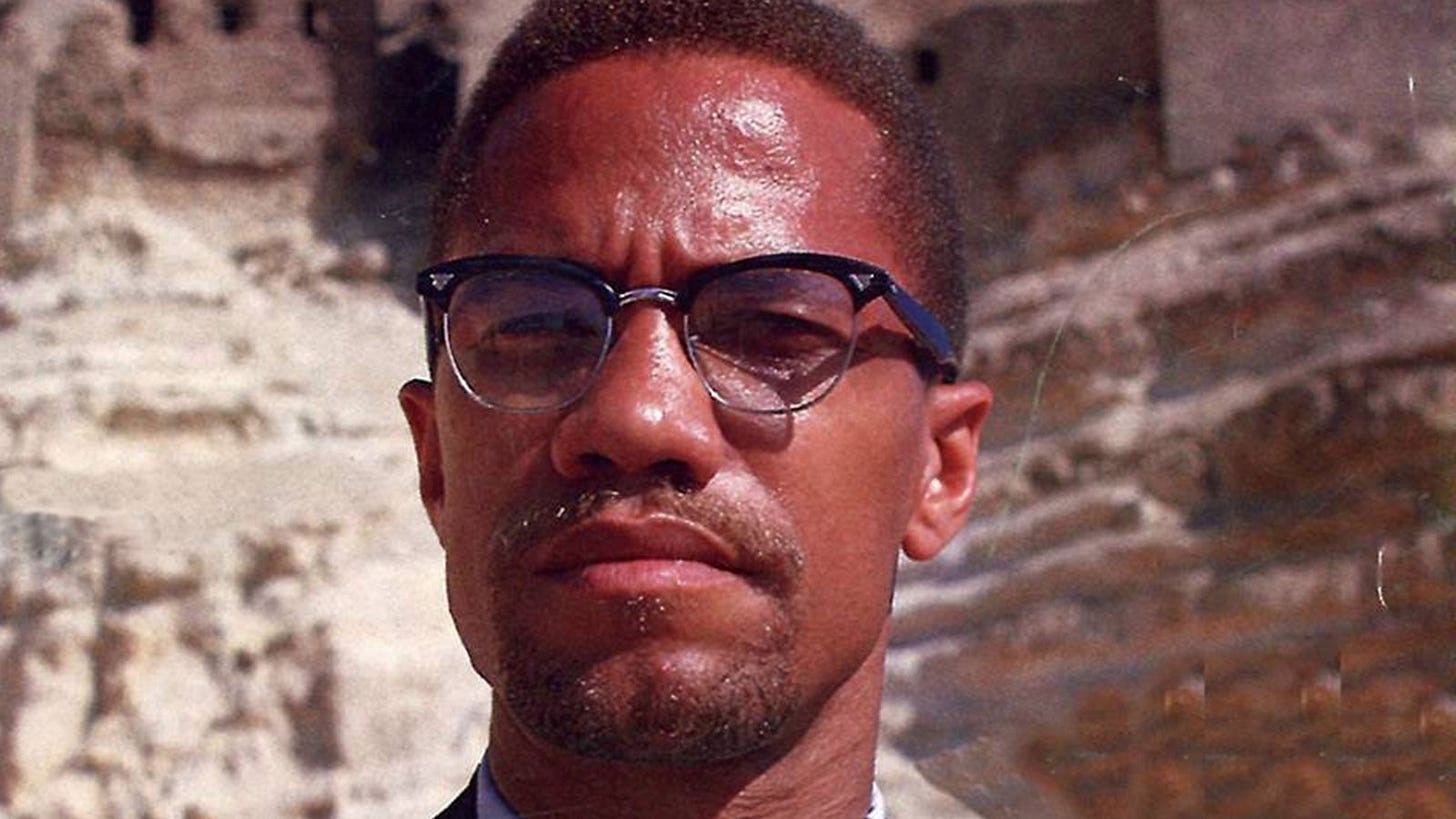

Today, on what would’ve been the 100th year of Malcolm X’s walk through this world, I return to that first copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, its spine cracked, margins underlined in feverish high school ink. I return to the boy I was when I found it: Black, restless, unknowing, hungry. A boy who didn’t yet have the language for rage or righteousness but knew he wanted to be free. A boy who believed in a God but hadn’t yet asked what that God believed in. A boy whose blood stirred when Malcolm spoke of dignity not as something granted by America, but as something we were born with, something we could reclaim by standing upright in the ruins.

That book did not just change me. It began me.

I’ve spent years now trying to articulate what Malcolm X meant to me and to so many others who were born into the fire and expected to become smoke. But words do not easily contain a man who refused containment. What I know is this: Malcolm was one of the most exacting and expansive leaders of the 20th century. He was our sharpest mirror and our most inconvenient love. He told the truth even when it endangered him, especially when it endangered him. And he did not just speak to Black America; he redefined what it meant to be Black and alive in a country built on our death.

Malcolm X did not ask to be adored. He asked to be understood. And when that failed, he made peace with being feared because in this country, the two are often inseparable for a Black man with a spine and a soul.

What I love most about Brother Malcolm was not simply his eloquence or militancy or swagger, though all of it sang like scripture, but his evolution. We often speak of revolution without remembering that it begins first with change inside a person. Malcolm never stopped growing. From Harlem to Mecca, from Nation to internationalist, he transformed publicly, painfully, beautifully. He taught us that changing one’s mind is not a weakness, it’s a kind of resurrection. A refusal to let dogma become coffin.

It is because of Malcolm that I fell in love with reading, not for escape but for resistance. Because of Malcolm, I understood faith not as submission but as struggle. Because of Malcolm, I began to advocate. I began to ask the questions school and church were afraid of. Because of Malcolm, I began to fall in love with my Blackness, with my voice, with the long tradition of our people who have always found a way to rise.

Malcolm X taught me that being Black is not a burden—it is a mandate. A calling. A chance to remake the world in the image of justice.

So today, I write this as a kind of love letter, not just to the man, the martyr, the father, the comrade but to all of you who carry his fire in your breath. Who wear your hair natural, your heart exposed, your politics sharp. Who love us enough to fight for us. Who will not let this nation forget what it did, or what it must become.

To the organizers. The students. The radical preachers. The poets. The mamas raising free Black children. The ones with nowhere to go but still moving. This is for you, too.

We are not alone in our grief or our hope. Malcolm lives wherever we do.

Let the record show: Brother Malcolm did not die begging. He died becoming.

Beautifully written. Malcolm X taught me something that literally no other Black man of his age and era ever said out loud in public. He spoke out loud about how badly Black women were treated.

While many Black men then and now behave as if Black women arrived as slaves on some other ships than the ones men arrived on, Malcolm X defined Black manhood on his terms when he said aloud, “How can we be respected as men when we let anything happen to our women.”

I also live by another Malcolm X dictum to “Never call any man brother until he demonstrates that he is one.”

I too loved that book. And yes, he never stopped evolving!